Symbols have been around for many years and it’s very rare for me to visit a school where they are not using one symbol set or another to support their students. From the earliest days when colleagues used to physically draw pictures over words with pencils, the use of symbols has provided support for early literacy, communication and served as a very useful tool for presenting information to visual learners. There is a strong evidence base which shows, where used appropriately; symbols aid the recognition, comprehension and retention of words.

Over the years, I must have trained hundreds of schools and organisations on the use of symbols to support communication and early literacy. My approach hasn’t changed much, and focuses firmly on encouraging colleagues to think carefully about whom they are writing for and the words that they choose to use before considering which (if any) symbol might be the most appropriate.

A typical training session would start with a game. I give each colleague a sheet of paper and a ‘secret’ word. Their task is to draw a picture that will communicate the ‘secret’ word to the group. I choose the secret words carefully, some nouns which are easy to draw such as car, bus and banana, some verbs such as running, eating and sleeping, again relatively easy to depict in a drawing. I’ll also throw in some more difficult to depict words such as mother, which and yesterday. As you can imagine, it’s a lot of fun trying to decipher the drawings to guess the words. The purpose of the exercise of course is to encourage those taking part to really think about the word I have given them and what they might need to draw to communicate the meaning of that word to their colleagues.

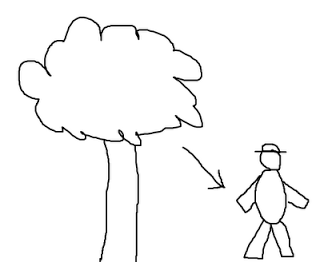

Here’s a real life example from a recent training session. Have a look at the drawing above. Can you guess the word that it is trying to communicate?

The word I gave the colleague was ‘HISTORY’

Did you work it out? No? Me neither.

The colleague who drew the picture explained that he found it incredibly difficult to come up with a picture that communicated the meaning of the word. “History”. He explained “history is about events that happened in the past and I couldn’t think of how to depict ‘the past’ in a way that my students who all have SLD / PMLD might be able to understand. So I drew a tree and man… ‘his tree’ get it? I put a bowler hat on the figure so you can tell it’s a man.”

This example illustrates quite nicely one of the difficulties we may encounter when we’re using symbols to add meaning to words. Quite simply, does the symbol we are using actually add meaning at all?

There are essentially three types of symbols.

- Symbols which we just know, pictures of things, for example car, tree, house, book.

- Symbols which can be worked out (decoded) for example big, jump, eat.

- Symbols depicting more abstract words which are difficult to work out and usually need to be taught, for example yesterday, went, going and of course history.

If we’re going to use symbols effectively, we need to consider the words we are using and who it is for. The next time you’re making symbol resources, take a moment to look at the symbol that’s popped up. Does it communicate the meaning of the word? If not, can you work it out? If the answer to both of these questions is no, you might want to reconsider the words you are using in your sentence or plan to teach your students what the symbol means. Remember, write for your audience and only choose symbols that add meaning. If you need to use more abstract words, be prepared to teach your students what the symbol actually means.

Symbols are just pictures. There I said it. There are no special magical properties about them, although sometimes when I talk to colleagues you might think otherwise. They are images that we use to help communicate meaning. Look at these three images.

They are all pictures of biscuits. One is a photograph; another is a drawing and the third a symbol from one of the common symbol sets. Are any of them ‘better’ than the others? Think about a student in your class and choose which symbol would be the most appropriate for them. Every time I have asked this question in my training courses the responses are as varied as the delegates who come to them. Many choose the photograph stating that it is the least abstract and most representative of the real object. Others choose the drawing saying that it’s clear and easier to see. Some choose the symbol because that’s what they use in school and their students are already familiar with it, but they all choose something different depending on the needs of their students. And that is the point.

It really doesn’t matter which picture you choose so long as your students can see it and understand what it means. Photographs, drawings and symbols are all appropriate so long as we all (staff and students) share an understanding of meaning behind them.

The most significant benefit of using a symbol set rather than ad-hoc pictures and photographs is the convenience they afford us. Symbol sets provide us with thousands of images each related to words and concepts all in one place. They usually come as part of an editing package which makes using them to create resources both quick and easy. Schools often choose a specific symbol package to meet their priorities, for example Boardmaker and PCS symbols to support communication, Symwriter and the Widget Literacy symbols to support early literacy or Makaton symbols which follow closely Makaton signing system. There are other symbol sets too each of which provide benefits to their users. Which you choose should reflect how you are going to use them. Some schools also decide a ‘core’ vocabulary and which symbols to use for each word to ensure consistency across school.

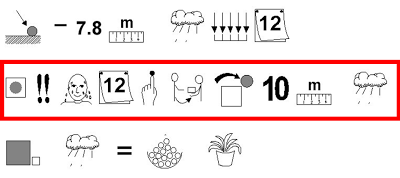

Let’s have a quiz. Here’s a sentence taken from a symbol supported website. I’ve removed the words; see if you can decode the sentence.

![]()

How well did you do? Maybe it would help to give you a couple of other sentences which might give you a clue as the context of the sentence.

Are you any closer to working it out? Remember that the symbols were added to this site to make it easier for people to read and understand it. It won an award for it! Give up?

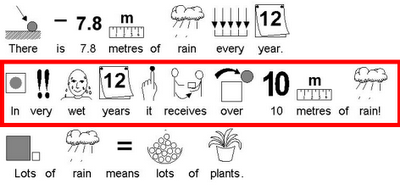

How many of the symbols did you just know? How many could you decode? Did any completely confuse you? The observant among you will also notice that two different symbols are used for the word ‘lots’ in the last sentence. I have no idea what that is about and it really only adds to the confusion.

The example above illustrates nicely the three different types of symbols. Let’s look again at the sentence and categorise them according to my results.

Symbols I just knew: ‘10’ for the number 10 (because I’m numerate) and ‘rain’ because I know that rain falls from clouds. I learned that in science.

Symbols I could work out: ‘in’, ‘over’. I did get ‘years’ but only because I know that there are 12 months in a year and the picture was a calendar, ‘metres’ because I know what a ruler is for and that the word ‘metre’ begins with the letter M. Oh and ‘wet’ although my first guess was ‘sweaty’.

The rest I had to look up as I didn’t know what they meant. Two exclamation marks for the word ‘very’ makes sense now but only because I understand the use of them in English grammar. Think of the skills and prior knowledge that was required to complete the exercise. Now imagine what one of your students might make of this sentence. Would they have the skills and background knowledge to decode the symbols and read the sentence?

Adding symbols, photographs or drawings to words doesn’t automatically add meaning to them. We need to think carefully about the sentences that we are constructing, add symbols to the words that convey information and choose those symbols wisely based on our knowledge of our student’s needs.

“What symbol do I use for ‘pursuant’?”

I recently delivered symbol training for an organisation that provided sheltered housing for people with learning difficulties. Like many organisations working in this sector they wanted to ensure that their written communications with their tenants were accessible. They purchased symbol processing software and asked me to help them. The training went the usual way. We looked at symbols and how / if they added meaning to the words they were representing. We talked about what the needs of their tenants might be and how we might need to differentiate the text for them.

After lunch, I set them a task. Identify something you might send to a tenant and produce an accessible version. That’s when I was asked the question, “what symbol do I use for pursuant?” The delegate explained that she often received notes from tenants asking if they were able to keep a pet. She even showed me one she had just received. It was handwritten and much as you would expect from someone with a severe learning difficulty. The text was barely readable and the tenant had drawn a picture of themselves with a dog. The delegate explained that the normal way to respond to requests to keep dogs was to write a letter refusing the request and quoting the relevant section from the tenancy agreement which began. “Pursuant to your rights as a tenant …”

The note from the tenant provided a perfect example of what the organisation needed to do. The sentence that the tenant had written was almost incomprehensible to most of us yet we all understood what it was she wanted. Why? Because the tenant had, in the picture she’d drawn provided ‘symbol’ support to help us decode the text. It was a powerful example of how we need to think about whom we are writing for, differentiate the sentences to meet their needs and use symbols only where they convey information and add meaning. The tenant hadn’t drawn pictures for the rest of the words she had written, “would like to have a “, just a picture of herself and the dog she wanted. We spent the afternoon working on responses to the note and by our last session of the day they had made significant progress in writing more appropriate sentences and using symbols only for those words that aided meaning.

It’s a popular misconception that simply adding symbols to text will make it easier for someone with learning difficulties to read and understand in much in the same way that converting complex sentences to speech is unlikely to make them any more accessible to someone with dyslexia. If we are to use symbols effectively, we need to be sure about our target audience. What are their reading levels? How many information carrying words can they cope with? Are they able to ‘hold’ enough information to be able to process a long sentence?

Throughout the training I emphasise this over and over again. Know who you are writing for and write sentences (and use symbols) which are appropriate to their needs. I always finish the day by asking delegates to write two sentences for me about what they have learned and how they will use it in their work. It’s a trick question. I want to see if they listened. The sentences are for ME. I can read and write. I don’t need simple sentences or symbols.

They always write simple sentences and use symbols.